Abstract

The connecting C-filaments of insect indirect flight muscles have been proposed as one of the elements providing muscle elasticity for the asynchronous muscle physiology of derived insects. Two large modular proteins, kettin/Sallimus and projectin make up these filaments, and for both proteins the N-terminal sequences span the extensible I-band and are proposed as the elastic segments. The C-filaments have not been studied in insects, such as dragonflies, crickets, and Lepidoptera with muscles which are largely synchronous in physiology and display different levels of muscle stiffness. In this paper we focus our efforts on the projectin protein of several insects with synchronous flight muscles; namely dragonfly, cricket, and moth. We provide evidence for the localization of projectin over the sarcomere I-Z-I region that is consistent with the existence of C-filaments in synchronous flight muscles. Additionally, we determine the sequences for the NH2-terminal region of projectin in these insects and describe the presence of alternative splice variants. Using predictors of intrinsically disordered regions, we identify possible unfolded segments, especially around the short linker sequences found between the NH2 Ig domains. We propose a possible picture of projectin NH2-terminal region organized as different segments contributing elastic responses to stretch by either unfolding of highly disordered sequences (PEVK) or reorientation of domains by bending or twisting of disordered linkers between the Ig domains.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Leonid Tarassishin, Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2012 Agnes Ayme-Southgate, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

The classical model of muscle contraction, described as the sliding filament model includes two filament systems based on the polymers of actin and myosin proteins. Additionally, the existence of a third elastic filament system is well documented both in vertebrates (titin filament; reviewed in 1) and in invertebrates. In insects, this filament, which is known as the connecting filament (C-filament) has been described in the Indirect Flight Muscles (IFMs) of several derived insect species, including Lethocerus indicus (waterbug), Apis mellifera (honeybee) and Drosophila melanogaster (reviewed in 2). The C-filaments provide a mechanical link between the Z-discs and the ends of the thick filaments and are composed of two large modular proteins, kettin/Sallimus3, 4, 5 (abbreviated as Sls), and projectin6, 7, 8. The C-filaments have been proposed as one of the elements generating muscle stiffness in the IFMs of derived insect, a property necessary for the stretch activation mechanism and asynchronous flight physiology (reviewed in 2, 9). These C-filaments have not, however, been studied in insect such as dragonflies, crickets, and Lepidoptera which use synchronous flight muscles and display different levels of muscle stiffness10, 11.

The molecular characterization of projectin available for several insects reveals a conserved organization with a specific pattern of repeated motifs and unique sequences12, 13, 14. The central region of the protein is composed of Fibronectin III (FnIII) and Immunoglobulin C (Ig) domains that are organized in fourteen repeated Fn modules, and are both capable of multiple protein-protein interactions. The NH2 terminus is composed of two tandem arrays of respectively eight and six Ig domains separated by a unique sequence, described as the PEVK-NTCS-1 region13.

In D. melanogaster IFMs the NH2-terminus of projectin is embedded within the Z-line, thus contributing to the anchoring of the C-filaments15. The exact number of Ig domains within the Z-line is unknown, but the present model for C-filament organization5 suggests that at least some of the NH2-terminal Ig domains would be outside of the Z-band and span the I-band region of the sarcomere. These domains could potentially contribute by their unfolding/reorganization to the extensibility of the projectin protein under stretch.

In D. melanogaster, the localization of projectin differs as it is found over the I-Z-I bands in asynchronous IFMs, but over the A band in synchronous muscles16. It is unclear whether this difference in localization is related to the asynchronous versus synchronous nature of the muscles or whether it is more generally a difference between flight and non-flight muscle organization. The localization of projectin in the flight muscles of insect orders with low passive stiffness and/or synchronous flight physiology has not been evaluated.

In this paper we describe the characterization of the NH2-terminal Ig domains of projectin across the span of insect evolution, including the prediction of their unfolded propensity. We demonstrate the presence of alternative splice variants producing shorter molecules, and we also provide evidence for the distribution of projectin within the sarcomere of a variety of insect flight muscles. These data are discussed in the context of a proposed model for projectin extensibility.

Materials and Methods

A) Insects and RNA Sample Preparation

Bombyx mori (Silk worm) and Manduca sexta (Carolina sphinx/tobacco hornworm) were purchased as larvae or cocoons from Educational Science (Tx). Pachydiplax longipennis (blue dasher, dragonfly) and Tibicen sp. (cicada) were caught from wild populations in Charleston, SC. Libellula pulchella (twelve-spotted skimmer dragonfly) were provided by Dr. J. Marden (Penn State University, PA). Acheta domesticus (cricket) were purchased from local pet stores.

Total RNA was purified from whole animals, isolated body parts (legs, heads), and from dissected thorax flight muscles using Trizol (Invitrogen™) as described before12.

B) Degenerated Primers and cDNA Sequence Determination

Multiple sequence alignments (MSA) of specific projectin regions available for several insects12, 13 were performed using the CLUSTALW algorithm17, 18. Degenerated primers were manually designed from nucleotides stretches showing the highest conservation. Primers used in this study are located within the two stretches of Ig domains found in the NH2-terminal region (Table 1).

RT-PCR reactions were performed as described before19 on the different RNA preparations using various combinations of the primers in Table 1. Annealing for both the RT and PCR reactions were tested in a range of temperatures to optimize each degenerated primer set. Resulting DNA fragments were isolated after agarose gel electrophoresis and subcloned into the pGEM-T shuttle vector (Promega, Inc.). They were then sequenced (Genewiz, Inc.) and the contigs assembled manually from the overlapping clones.

Table 1. Sequence and position of degenerated primers used in this study. Several sequences were used to derive both forward and reverse primers, e.g. Ntd2/2R with the reverse denoted as R. The provided sequence is that of the forward strand. N = any base; S = G or C; Y = C or T; R = A or G; M = A or C (IUPAC nucleotide code).| Primer | Sequence | Position |

|---|---|---|

| Ntd1 | GTIGCIGAMGAYTTCGCKCCBAGC | Ig1 |

| Ntd2/2R | CAAATYGAYGGWNTNGCNCCRAC | Ig2 |

| Ntd3/3R | CCNACNTTYACNGAAMGRCC | Ig3 |

| Ntd4 | GGYGARAGYAAYGCMAACATIKC | Ig4 |

| Ntd5 | GAACCNGAAGGAGASGGNCC | Ig5 |

| Ntd8/8R | GGNGARCTNAAYGCSAATYYNAC | Ig6 |

| Ntd9/9R | GAGGGNGARTTYGCNGTNAARTTNG | Ig8 |

| Nt6d1R | GTARAATTTGAAYGTMGGNGCNGG | Ig9 |

| N3F/N3 | GCACGGAAGTCCATACCGCTGG | FRAM |

| Nt6d2/2R | CCNAATTGCAAACCAAAATGG | Ig10 |

| Nt6d5/5R | GARCTNCAAGATCAAACAGC | Ig12 |

| Nt6d6/6R | GAAGCNAAACTCTTGAAAGACGG | Ig13 |

| Cored1R | GGTGGTTCACCTATAMCNMAATAYG | Fnl |

C) Bioinformatics Analysis

Sequence comparisons were carried out using the CLUSTALW algorithm17, 18 and the alignments were viewed in Jalview20. Pairwise homology scores generated by CLUSTALW were used to calculate the average degree of conservation for each individual Ig domain. Intrinsic disorder predictions were also carried out using three predictor software, IUPRED 21, 22, FoldIndex23 , and PONDR-FIT24.

D) Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Dissected flight muscles or half thoraces were quick frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) medium at – 20oC and 10 μM slices were sectioned using a Thermo Scientific Microm HM550 cryostat. Alternatively, individual muscle fibers were cut from dissected flight muscles and directly immobilized on subbed microscope glass slides using hand pressure on a coverslip. Sections or squashes were fixed immediately and the slides processed for immunofluorescence microscopy as described previously25. For double labeling, the two primary antibodies from different species were applied together, as were the two animal-specific secondary antibodies. Both Cy5 and fluorescein-tagged secondary antibodies were used for identification. F-actin was stained using phalloidin-FITC or RITC (Sigma) diluted 1:100 together with the secondary antibody. Slides were mounted in mounting medium (Vectorshield, Inc.). All slides were examined by epifluorescence microscopy on an Olympus 1X81 spinning disk confocal microscope. All immunofluorescence experiment preparations treated with secondary antibodies alone showed no background staining. Images were captured and analyzed using Olympus Slidebook software.

Antibodies

Anti-projectin: Mac15026, Core-1P25, 3b11 and P57, 8, NT2 (derived against a fusion protein representing Ig 9 and Ig10) and anti-FRAM (prepared against a synthesized oligopeptide, Invitrogen).

anti-kettin: Mac155, Anti-actinin: Mac27626 and 4g6 7, 8.

The “Mac” antibodies are rat monoclonals (generous gift from Dr. Belinda Bullard, EMBL, Heidelberg). 3b11, P5, and 4g6 are mouse monoclonal antibodies (generous gift from Dr. Judith Saide, BU School of Medicine, Boston); Core-1P, NT2, and anti-FRAM are rabbit polyclonal antibodies.

Results

Partial Sequence Identification in Moth, Dragonfly, Cricket and Cicada

We recently completed the annotation of the full Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) projectin gene using sequences available from GenBank, with the analysis of its PEVK domain described elsewhere14. Some insect projectin sequences used in this study for comparison have been previously described12, 13, 14. The phylogenetic relationship and flight muscle physiology of the insects included in this study, as well as the status of their projectin sequences are summarized in Figure 1

Figure 1.Phylogenetic relationship and flight muscle physiology of the insects included in this study. For the insects labeled in red, the sequences of projectin NH2-terminus were obtained for this study. For the insect species labeled in gray, the projectin sequence is complete and the initial annotation has already been described.

Using a collection of degenerated primers covering the NH2-terminal Ig domains, initial RT-PCR amplification products were generated for two dragonfly species (P. longipennis and L. pulchella), as well as one cicada (Tibicen sp.) and one cricket (A. domesticus). Sequences were completed by designing species-specific primers to fill-in any remaining sequence gaps, as well as the original degenerated primers. These analyses provide us with the corresponding complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences for the two stretches of Ig domains flanking the PEVK region, which we referred to as the N8Ig and N6Ig regions.

Sequence Analysis of the NIg Segments

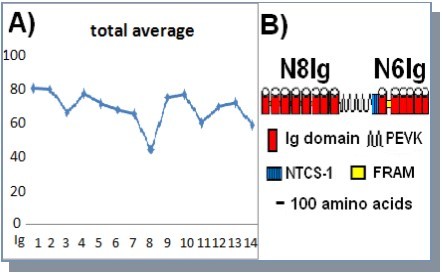

The N8Ig and N6Ig sequences were split into their individual domains, and all the domains at a specific position, e.g. all Ig1, were aligned with each other using CLUSTAL-W. The pairwise homology scores generated by the multiple alignment analysis were used to generate an average homology score for each domain. As presented in Figure 2, the average degree of conservation for individual Ig domain varies, with the highest level for Ig1 and Ig2 (80%), falling to only 43% for Ig8 just before the PEVK extensible region. The six Ig domains of N6Ig and the unique FRAM linker sequence between Ig9 and Ig10 show an intermediate level of conservation from 76 to 58% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.Organization and conservation of the NH2-terminal region. A) Average degree of amino acid conservation for individual Ig domains in the N8Ig and N6Ig regions. B) Schematic of the NH2-terminus region of insect projectin.

The alignments for each of the Ig domains were also compared to the Ig consensus sequence originally defined for the Ig domain of C. elegans twitchin27. When only the amino acids at these consensus positions (black areas in Figure 3A) are examined, the level of conservation for residues of the consensus sequence is similar for all the Ig domains, from 17 to 21 amino acids out of 37 consensus residues. There is also a strong conservation of non-consensus amino acids at both ends of each domain except for Ig8. Most of the variability between domains can be accounted for by a decreased conservation of residues within the central portion of the domain as exemplified by the differences between Ig1 (80%) and Ig3 (65%). Based on X-ray crystallography or NMR studies of both titin and twitchin Ig domains, the central amino acids correspond to loop D-E, helix E, and loop E-F on the crystal structures of various titin and twitchin domains (Figure 3B). This central domain is variable in both sequence and length in different titin Ig domains, but tends to protrude from the central nucleus of the domain28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 as shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.Sequence alignment for selected Ig domains A) CLUSTAL-W alignment of Ig1, 3, 5 and 8 for different insects. Shading of gray indicates the extent of conservation. Black bars represent conserved consensus amino acids with the consensus provided below each Ig group. Lpul = Libellula pulchella, Plon = Pachydyplax longipennis, Adom= Acheta domesticus, Phum = Pediculus humanus, Api = Acyrthosiphon pisum, Tib = Tibicen sp., Tca = Tribolium castaneum, Ame = Apis mellifera, Msex = Manduca sexta, Bmo = Bombyx mori, and Dmel= Drosophila melanogaster. B) Structure from solution NMR data for titin Ig 27 from the Molecular Modeling Database (MMDB Accession # 1TIU) with loop D-E, helix E, and loop E-F highlighted33.

The analysis of the alignment for the second stretch of domains (the N6Ig) reveals a similar pattern of conservation of consensus and non-consensus residues at each ends of the domain and a more variable central domain (data not shown). The N6Ig domain between Ig 9 and Ig 10 also contains a unique sequence known as FRAM, which is 46 amino acid long and shows 76% overall homology for all the insects included in this study.

The conservation of the consensus residues suggest that the projectin N-terminal Ig domains could adopt the Ig fold as described for several titin Ig domains28, 29. However several Ig domains of the titin protein have also been extensively studied in relation with their unfolding behavior under stretch, which is capable of generating both secondary and tertiary elasticity (reviewed in 34). Because some of the projectin N8Ig domains may belong to the extensible region of the molecule, we also evaluated the likelihood of unfolding for these NH2-terminal Ig domains, by predicting the propensity of the amino acid sequences to be natively disordered. We used several predictors of intrinsically disordered domains (IDPs) and present in Figure 4 the analysis for one predictor, Foldindex23 for the first 8 Ig domains of representative insect species. Predictions for IDP using IUPRED21, 22 and PONDR-FIT24 were also performed and can be found in Supplemental Materials. Even though the detailed patterns are different between species and predictors, there are certain regions that are consistently predicted as disordered across all analyzed insects and all predictors. These regions localize at the borders between some of the Ig domains and typically encompass the short linker sequences present between Ig domains (Red arrows in Figure 4). These linkers are short, ranging from four to eleven amino acids and are typically well conserved between insects. Only two linkers in A. mellifera and one in L. pulchella are predicted to be folded (Green arrows in Figure 4). Figure 4 also offers a similar analysis for the first two Ig domains of titin, named Z1/Z2 and the six amino acid linker sequence found between them. Interestingly, the short linker between the two titin Ig domains is also predicted to be intrinsically disordered, whereas the Ig domains themselves have a highly ordered propensity consistent with the X-ray crystallography data35, 36.

Figure 4.Prediction of unfolded segments in the N8Ig projectin region. The sequences were analyzed using the FoldIndex predictor. Each panel represents the analysis for one species as indicated in the top right of each panel. Positions of linkers are indicated by arrows, with their position based on their coordinates within the N8Ig sequences.

In D. melanogaster there are two alternative exons19 for the linker between Ig1 and Ig2, noted as linker 1a and 1b in Figure 4 top panel. As shown in the top panel of Figure 4, the two forms behave differently as one variant (1a) is predicted to be more disordered than the other (1b, insert in top panel). This same difference in disordered behavior is also detected by IUPRED and PONDR-FIT predictors. In the other species only one Ig1-Ig2 linker has been found by annotation and corresponds in sequence to linker 1a, the most disordered one from D. melanogaster. The existence in other insects of a second linker cannot be excluded even though in the species for which genomic data are available, the intronic regions where that linker should be found were searched extensively by BLAST, as well as manually. So unless the sequence of the second linker is extremely different from the one in Drosophila, it probably does not exist in the other species.

A similar analysis of the N6Ig region also predicts an extended region to be unfolded; it encompasses the end of Ig9, the totality of the FRAM region and approximately half of Ig10 (see Figure 2 for domain arrangement, data not shown).

Alternative Splicing in the N-Terminal Ig Domains

The conservation at the amino acid level at the beginning of the protein is reinforced at the gene level where the exon-intron pattern of the first four Ig domains is identical in all insects for which genomic sequences are available except in Lepidopterawhere exon #1 is split into 2 exons. On the other hand, the exon-intron pattern of the next four Ig domains is divergent with multiple events of intron loss or acquisition (Figure 5). When the rest of the projectin gene is considered there is overall very little conservation of the exon-intron pattern as reported before and reinforced by the highly variable number of total exons12, 13.

Figure 5.The exon-intron pattern is conserved at the beginning of the N8Ig region. Diagram depicts the position of splice sites in insects for which genomic sequences are available. Black and gray boxes represent exons for alternating Ig domains. Intron sizes are not to scale.

This exon-intron pattern theoretically allows for two alternative splicing patterns, which both conserve the open reading frame, and lead to the precise removal of two (Ig #3 and 4; referred to as Δ3-4) or three (Ig# 2, 3 and 4) domains. The actual use of these alternate splicing patterns was tested for all insects in RT-PCR reactions using forward primers from the Ig 1 or Ig2 domains and reverse primer from the Ig5 domain. Predicted differences in the size of the amplified products allow clear identification of the “full” product (containing Ig3 and Ig4 domains) or the alternative splice variant Δ3-4. We also tested whether the alternate splice options were muscle-type specific, by performing the RT-PCR reactions from RNA isolated from leg, head and flight muscles. Evidence of the alternate Δ3-4 variant was obtained for all tested insects and all muscle types, except in M. sexta where the Δ3-4 variant is absent from the flight muscles. The amplified products were sequenced, confirming that the shorter cDNA product corresponds to an in-frame removal of Ig3 and Ig4 (Δ3-4). Representative data for M. sexta and Tibicen sp. are presented in Figure 6 and the complete analysis is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6.The N8Ig region undergoes alternative splicing. RT-PCR were run with RNA extracted from different body parts using primers located in Ig 1 and Ig5 as indicated on the diagram below the electrophoresis figures. Short range and long range DNA ladders are in lanes one and two. H = head, L = leg, T = thorax and F = flight. The presence of a shorter product is denoted as Δ3-4 in all samples whereas FULL indicates the amplification product for the complete Ig1-Ig5 segment.

| Species | Pachidyplax | Tibicen | Apis | Manduca | Drosophila | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Parts | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight |

| With Ig3+4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| w/o Ig3+4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NO | Yes |

| Species | Pachidyplax | Acheta | Apis | Manduca | Drosophila | |||||

| Body Parts | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight | Leg | Flight |

| With Ig9 and FRAM | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| w/o Ig9 and FRAM | Yes | NO | n/a | NO | n/a | n/a | NO | NO | Yes | Yes |

In the Manduca sexta analysis, the Δ3-4 variant is clearly amplified as a 439 bp product in lanes from head, leg and thorax RNA, but is absent from flight muscle RNA. The full product at 1,081 bp is also visible in all but the head lane. However longer RT-PCR products are often underrepresented in reactions where a smaller product is amplified. The Tibicensp analysis indicates the presence of the Δ3-4 variant (252 bp) in all muscle types. Again the full product (894 bp) is underrepresented in this analysis and can only be detected in the thorax lane. RT-PCR reactions using primers within the Ig3 and 4 domains indicate that the full length transcript is present in all muscle tissues, even though its amplification is not always evident when using primers from Ig1 or Ig2 and Ig5 as the shorter alternate form can be preferentially amplified in RT-PCR reactions.

A similar analysis to test for the alternate removal of Ig2+3+4 did not reveal the existence of this alternate option in any of the species tested and any of the muscle types (data not shown). This does not preclude, however, that this variant is used in other muscles such as larval or embryonic tissues.

The highly conserved FRAM domain was also shown to be alternatively spliced at least in some of the insects included in this study. In the dragonfly P. longipennis, an alternate

variant without Ig9 and FRAM (referred to as ΔIg9-FRAM) is found in leg and head muscles but not in flight muscles (Table 2). The ΔIg9-FRAM variant was also detected in all muscle types of D. melanogaster, but could not be amplified in any muscles preparation of M. sextaor A. domesticus. We could not detect it from A. mellifera, but this might be more related to the fact that in A. mellifera flight muscles, the PEVK domain is extremely short13 (~ 100bp), and the amplified product (typically from Ig8 to Ig10) would be rendered even shorter by removing the exon containing the end of PEVK and beginning of Ig9. Data for the ΔIg9-FRAM variant are summarized in Table 2. It might be particularly relevant that the only flight muscles where the ΔIg9-FRAM has been detected are the asynchronous flight muscles of D. melanogaster.

Myofibrillar Localization of Projectin

Some of the insects included in this study were also analyzed for projectin sarcomeric localization in flight muscles because in Drosophila melanogaster, projectin localization is different in synchronous muscles compared to asynchronous flight muscles. In synchronous muscles such as leg and Larva body wall, projectin co-localizes with myosin over the A-band, whereas it is associated with the I-Z-I region and the C-filaments in asynchronous flight16. The question is whether in synchronous flight muscles such as these of the dragonfly, cricket and moths, projectin will still be associated with the I-Z-I domain, and be a component of C-filaments or follow its synchronous A band pattern. Several projectin antibodies for which the epitope localization is known were used in order to ascertain the myofibrillar position of the protein (See Materials and Methods for list of antibodies). The localization was established in comparison with actin detected by phalloidin staining, and several other proteins, such as α-actinin and kettin using specific antibodies7, 8, 26.

In the dragonfly P. longipennis, projectin N-terminus detected with antibodies P5 (Figure 7A) and NT2 (not shown) co-localizes with kettin at the I-Z-I band, whereas a C-terminus epitope (3b11) does not (Figure 7B). This distribution indicates that in dragonfly flight muscles, projectin has a similar topography to the one described in more derived insects such as D. melanogaster and A. mellifera6, 7, 8. Figures 7C-E present images for M. sextaflight muscleswith the colocalization of projectin epitopes and α-actinin, as well as two projectin epitopes (7E). In this latter case the muscles might have been slightly stretched during the preparation and there is a splitting of the signal (white arrows in 7E), probably representing the two projectin filaments from adjacent sarcomeres protruding on both sides of the Z-band. In Figure 7F and Figure 7G the visualization of cricket projectin shows that the projectin epitopes are again associated with the I-Z-I band. The images also reveal a splitting of the signal (white arrows in F and G), which is wider and more commonly observed than in the M. sexta images. This may indicate a stretch of the muscles during preparation or possibly a longer sarcomere allowing for better separation of epitopes.

The pattern in all three insects is consistent with the presence of connecting C-filaments in insect flight muscles with synchronous physiology, and even in species which are considered basal phylogenetically (like dragonfly).

Figure 7.Projectin is positioned over the I-Z-I region in synchronous flight muscles. Images are from double epifluorescence microscopy staining each muscle tissue with an antibody against a projectin epitope (left panel) and another protein (middle panel). The photographs in the right panel represent the merged images. Proteins and their respective antibodies are indicated on the far right of each set of three photographs. The arrows indicate incidence of signal splitting for projectin. Bar represents 10 µm in all photographs. A and B) localization in P. longipennis (dragonfly) ; C-E) localization in M. sexta (moth); and F and G) localization in A. domesticus (cricket).

Discussion

Connecting (C)-filaments are elastic protein structures that are proposed to be involved in “stretch activation” of asynchronous IFMs in derived insects2, 5, 6, 37, 38, 39, 40. Because both projectin and kettin/Sls are components of the C-filaments, they contribute to the high resting tension of the IFM fibers and must contain elastic elements4, 41, 42. To perform such a function, projectin would need to be anchored at the Z band through its NH2-terminus and attached with the thick filaments as illustrated in Figure 8A. The projectin protein would also most likely contain segments that can change length in response to physiological stretch.

Figure 8.Proposed model of projectin elasticity. A) Schematic of the muscle sarcomere indicating the proposed position of projectin and kettin/Sls as part of the C-filaments (modified from ref. 5). Projectin NH2-terminus would be spanning the I band extensible region. B) Proposed model for unfolding of different segments and rearrangement of Ig domains under stretch. C) Schematic of the shortening accomplished by the use of alternative variants. The existence of molecules combining all three splicing options is unknown.

In the IFMs, projectin is found in the sarcomere I-Z-I region as part of the C-filaments, but is found by immunofluorescence microscopy over the A band in synchronous muscles16. The question arises whether the A band localization is associated with synchronous physiology and whether in synchronous flight muscles such as dragonfly and cricket projectin would be localized over the A band. We evaluated the localization of projectin in the flight muscles of several insects with synchronous flight physiology and established that in these flight muscles, projectin is localized over the I-Z-I domain and co-localizes with kettin and α-actinin. Therefore the position of projectin over the I-Z-I region and its inclusion into the C-filaments are characteristics of flight muscles irrespective of their asynchronous or synchronous nature.

The overall domain organization of projectin is conserved not just in insects, but at least in one other arthropod for which sequences are available, the crayfish43. Crayfish projectin however contains only seven Ig domains in the first NH2 Ig stretch of the protein, whereas all insect projectin proteins characterized so far contain eight NH2-terminal Ig domains. The increase to eight Ig domains must have occurred very early in the insect lineage or before as it is now established by our studies in dragonfly (an order considered basal in the insect phylogenetic lineage; Figure 1) and in the silverfish (Apterygote; order Zygentoma/Thysanura; R. Southgate, unpublished observation). Of the first eight Ig domains of the projectin protein, the first seven domains are well conserved (Figure 2 and Figure 3) indicating that these domains might need conserved surfaces to interact with other proteins and ensure the anchoring of projectin to Z-band proteins, as well as to kettin in the C-filaments and/or actin. The eighth domain is much less conserved, and even though we cannot exclude possible interactions with other proteins, its function might also be to provide additional length to the protein and hence the C-filaments, and/or serve as a transition/damper domain between the N8Ig region and the highly disordered, unfolding-prone PEVK region, which immediately follows.

Predictions of intrinsically disordered regions indicate that several segments could be, at least partially, unfolded, in particular the linker regions between the Ig domains. Recent studies of titin Z1-Z2 Ig domains have indicated that the orientation of these two domains in respect with each other could change under stretch and that mechanical elasticity could result from bending and twisting of the linker region34, 35, 36. In our analysis the six amino acid linker between Z1 and Z2 is predicted as disordered. It is tempting to speculate that the disordered linkers found between the different Ig domains of NH2-terminal projectin could play a similar role and provide the so-called “tertiary structure” elasticity34, 44. The relative orientation of adjacent domains would be controlled by the bending and twisting of the respective linker, as well as possible Ig domain interactions, which is where Ig sequence conservation could also play a role. This would provide the possibility of molecule extension under relative low force as illustrated in the model proposed in Figure 8B. The extent of this elongation could also be partially modulated by the existence of the Δ3-4 alternate splice variant, which is shorter by two Ig domains and two linkers (see Figure 8B and Figure 8C). This idea of combining intrinsic disorder and alternative splicing to increase protein plasticity has already been tested for a large number of proteins from the SwissProt database showing that protein segments undergoing alternative splicing are more often also intrinsically disordered, allowing a range of functional diversity without conformational constraints45.

The N8Ig region is followed by a PEVK segment, which has been postulated to have the ability to reversibly unfold under low forces and its length is also controlled by extensive alternative splicing events12, 13, 14 (Figure 8B and Figure 8C). The PEVK is followed by a second stretch of six Ig domains (N6Ig), with a unique segment known as FRAM between Ig9 and 10. The FRAM sequence is a highly conserved sequence, but is also predicted to be highly disordered together with the beginning of the following Ig domain. This FRAM-Ig10 disordered region could provide an additional extensible segment with elasticity at low forces. The presence of an alternative splice variant removing the Ig9-FRAM region could again provide flexibility for the range of extension achieved by the molecule.

Conclusions

A picture is starting to emerge of the possible organization of projectin NH2 terminal region with the length of the molecule and therefore its elastic contribution controlled both by alternative splicing events creating shorter variants (Figure 8C) and by unfolding of highly disordered sequences (PEVK) or reorientation of Ig domains through bending or twisting of disordered linkers in the N8Ig and N6Ig regions following stretch (Figure 8B).

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the College of Charleston faculty (to AAS) and undergraduate research (to MC) grants. We want to thank Dr. J. Marden for providing the L. pulchella samples.

References

- 1.H L Granzier, Labeit S. (2005) Titin and its associated proteins: the third myofilament system of the sarcomere. , Adv. Protein Chem 71, 89-119.

- 2.Trombitas K. (2000) Connecting filaments: a historical prospective. In:. Elastic Filaments of the Cell Proceedings, Pollack GH, Granzier H, eds.Kluwer Academic/PlenumPublishers .

- 3.Bullard B, Linke W, Leonard K. (2002) Varieties of elastic protein in invertebrate muscles. , J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 23, 435-447.

- 4.Bullard B, Goulding D, Ferguson C, Leonard K. (2000) Links in the chain: the contribution of kettin to the elasticity of insect muscles. In:. Elastic Filaments of the Cell Proceedings, Pollack GH, Granzier H, eds.Kluwer Academic/PlenumPublishers .

- 5.Bullard B, Burkart C, Labeit S, Leonard K. (2005) The function of elastic proteins in the oscillatory contractions of insect flight muscle. , J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 26, 479-485.

- 6.Saide J D. (1981) Identification of a Connecting Filament Protein in Insect Fibrillar Flight Muscle. , J. Mol. Biol 153, 661-679.

- 7.J D Saide, Chin-Bow S, Hogan-Sheldon J, Busquets-Turner L, J O Vigoreaux. (1989) Characterization of Components of Z-Bands in the Fibrillar Flight Muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. , J. Cell Biol 109, 2157-2167.

- 8.J D Saide, Chin-Bow S, Hogan-Sheldon J, Busquets-Turner L. (1990) Z band proteins in the flight muscle and leg muscle of the honeybee. , J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 11, 125-136.

- 9.R K Josephson, J G Malamud, D R Stokes. (2000) Asynchronous Muscles: A Primer. , J. Exp. Biol 203, 2713-2722.

- 10.Peckham M, White D C S. (1991) Mechanical properties of demembranated flight muscle fibers from a dragonfly. , J. Exp. Biol 159, 135-147.

- 11.Peckham M, Cripps R, White D, Bullard B. (1992) Mechanics and protein content of insect flight muscles. , J. Exp. Biol 168, 57-76.

- 12.Ayme-Southgate A, Southgate R J, Philipp R A, Sotka A A, Kramp C. (2008) The myofibrillar protein, projectin, is highly conserved across insect evolution except for its PEVK domain. , J. Mol. Evol 67(6), 653-669.

- 13.Ayme-Southgate A, Philipp R A, Southgate R J. (2011) The projectin PEVK domain, splicing variants and domain structure in basal and derived insects. , J.Insect Mol.Biol 20(3), 347-356.

- 14.Ayme-Southgate A J, Turner L, Southgate R J. (2012) Molecular analysis of the muscle protein, projectin in Lepidoptera. , J. Insect Sci. (accepted)

- 15.Ayme-Southgate A, Saide J, Southgate R, Bounaix C, Camarato A. (2005) In indirect flight muscles Drosophila projectin has a short PEVK domain, and its NH2-terminus is embedded at the Z-band. , J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 26, 467-477.

- 16.J O Vigoreaux, J D Saide, M L Pardue. (1991) Structurally Different Drosophila Striated Muscles Utilize Distinct Variants of Z-Band Associated Proteins. , J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil 12, 340-354.

- 17.J D Thompson, D G Higgins, T J Gibson. (1994) CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. , Nucleic Acids Res 22, 4673-4680.

- 18.J D Thompson, T J Gibson, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, D G Higgins. (1997) The CLUSTAL X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. , Nucleic Acids Res 25, 4876-4882.

- 19.Southgate R, Ayme-Southgate A. (2001) Drosophila projectin contains a spring-like PEVK region which is alternatively spliced. , J. Mol. Biol 313, 1037-1045.

- 20.Waterhouse A M, Procter J B, DMA Martin, Clamp M, Barton G J. (2009) Jalview Version 2 - a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench". , Bioinformatics 25(9), 1189-1191.

- 21.Dosztányi Z, Csizmók V, Tompa P, Simon I. (2005) The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. , J. Mol. Biol 347(4), 827-39.

- 22.Dosztányi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. (2005) IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. , Bioinformatics 21(16), 3433-4.

- 23.Prilusky J, C E Felder, Zeev-Ben-Mordehai T, E H Rydberg, Man O. (2005) FoldIndex: a simple tool to predict whether a given protein sequence is intrinsically unfolded. , Bioinformatics 21(16), 3435-8.

- 24.Xue B, R L Dunbrack, R W Williams, A K Dunker, V N Uversky. (2010) PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. , Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804(4), 996-1010.

- 25.Ayme-Southgate A, Bounaix C, T E Riebe, Southgate R. (2004) Assembly of the Giant Protein Projectin During Myofibrillogenesis In Drosophila Indirect Flight Muscles. , Biol. Med. Central Cell Biol 5, 17-28.

- 26.Lakey A, Ferguson C, Labeit S, Reedy M, Larkins A. (1990) Identification and Localization of High Molecular Weight Proteins in Insect Flight and Leg Muscles. , EMBO J 9, 3459-3467.

- 27.G M Benian, J E Kiff, Neckelmann N, D G Moerman, R H Waterston. (1989) Sequence Of An Unusually Large Protein Implicated In Regulation Of Myosin Activity In. , C. elegans. Nature 342, 45-50.

- 28.Pfuhl M, Pastore A. (1995) Tertiary Structure of an Immunoglobulin- Like Domain from the Giant Muscle Protein Titin: a New Member of the I Set. , Curr. Biol 3, 391-401.

- 29.Pfuhl M, Improta S, A S Politou, Pastore A. (1997) When a Module is Also a Domain: The Rôle of the N Terminus in the Stability and the Dynamics of Immunoglobulin Domains from Titin. , J. Mol. Biol 265, 242-256.

- 30.Fong S, S J Hamill, Proctor M, Freund S M V, G M Benian. (1996) Structure and Stability of an Immunoglobulin Domain from Twitchin, a Muscle Protein of the Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. , J. Mol. Biol 264, 624-639.

- 31.Improta S, J K Krueger, Gautel M, R A Atkinson, J F Lefevre. (1998) The assembly of immunoglobulin-like modules in titin: implications for muscle elasticity. , J. Mol. Biol 284, 761-777.

- 32.S B Fowler, Clarke J. (2001) Mapping the folding pathway of an immunoglobulin domain: structural detail from Phi value analysis and movement of the transition state. , Structure 9(5), 355-66.

- 33.Improta S, A S Politou, Pastore A. (1996) Immunoglobulin-like modules from titin I-band: extensible components of muscle elasticity. , Structure 4(3), 323-37.

- 34.Hsin J, Strümpfer J, E H Lee, Schukten K. (2011) Molecular origin of the hierarchical elasticity of titin: simulation, experiment, and theory. , Annu. Rev. Biopys 40, 187-203.

- 35.Marino M, Zou P, Svergun D, Garcia P, Edlich C. (2006) The Ig doublet Z1Z2: a model system for the hybrid analysis of conformational dynamics in Ig tandems from titin. , Structure 4(9), 1437-47.

- 36.E H Lee, Hsin J, Mayans O, Schulten K. (2007) Secondary and tertiary structure elasticity of titin Z1Z2 and a titin chain model. , Biophys. J 93(5), 1719-35.

- 37.J F Deatherage, Cheng N, Bullard B. (1989) Arrangement of filaments and cross-links in the bee flight muscle Z disk by image analysis of oblique sections. , J. Cell Biol 108, 1775-1782.

- 38.H L Granzier, Wang K. (1993) Passive tension and stiffness of vertebrate skeletal and insect flight muscles: the contribution of weak cross-bridges and elastic filaments. , Biophys. J 65, 2141-2159.

- 39.H L Granzier, Wang K. (1993) Interplay between passive tension and strong and weak binding cross-bridges in insect indirect flight muscles. A functional dissection by gelsolin-mediated thin filament removal. , J. Gen. Physiol 101, 235-270.

- 40.M H Dickinson, Lighton J R B. (1995) Muscle efficiency and elastic storage in the flight motor of Drosophila. , Science 268, 87-90.

- 41.J R Moore, J O Vigoreaux, D W Maughan. (1999) The Drosophila projectin mutant, bentD, has reduced stretch activation and altered flight muscle kinetics. , J. Musc. Res. Cell Motil 20, 797-806.

- 42.J O Vigoreaux, J R Moore, D W Maughan. (2000) Role of the elastic protein projectin in stretch activation and work output of Drosophila flight muscles. In:. Elastic Filaments of the Cell Proceedings, Pollack GH, Granzier H, eds.Kluwer Academic/PlenumPublishers .

- 43.Oshino T, Shimamura J, Fukuzawa A, Maruyama K, Kimura S. (2003) The entire cDNA sequences of projectin isoforms of crayfish claw closer and flexor muscles and their localization. , J. Muscle Res. Cell. Motil 24(7), 431-438.

Cited by (3)

- 1.Yuan Chen-Ching, Ma Weikang, Schemmel Peter, Cheng Yu-Shu, Liu Jiangmin, et al, 2015, Elastic proteins in the flight muscle of Manduca sexta, Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 568(), 16, 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.033

- 2.Ayme-Southgate Agnes, Feldman Samuel, Fulmer Diana, 2015, Myofilament proteins in the synchronous flight muscles of Manduca sexta show both similarities and differences to Drosophila melanogaster, Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 62(), 174, 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.02.008

- 3.Gong Henry, Ma Weikang, Chen Shaoshuai, Wang Geng, Khairallah Ramzi, et al, 2020, Localization of the Elastic Proteins in the Flight Muscle of Manduca sexta, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(15), 5504, 10.3390/ijms21155504